We’re stuck at a roadblock on the way to Machu Picchu, and our taxi driver, Wilbert, is up a tree picking mangoes.

“This is bad,” I say, frustrated.

“We’ll figure something out,” Brendan replies, taking a bite out of a mango as if it were an apple.

We wait on a narrow strip of tarmac bordered by vibrant green jungle and sunlit mountains. Protesters, their faces tense and eyes anxious, gather around a barricade of boulders, logs, and branches. The women wear traditional bowler hats and colorful, intricately trimmed skirts called polleras. The men, dressed in baseball caps and football jerseys, converse in Quechua and Spanish. Instead of weapons, they hold hand-painted signs demanding unity and an end to corruption. Watching them, I feel torn between irritation at the delay and guilt for my privilege—this is their life; for us, it’s just a summer adventure.

“Do you want one?” Wilbert tosses another mango our way. I shake my head, baffled by the lack of urgency. Time seems to have stopped, and no one else seems bothered.

I’m traveling with Bets, a friend from Melbourne, and two Irish backpackers, Brendan and Brian. We met at a hostel in Cusco, bonding over beer pong and late-night conversations about everything from Spanish imperialism to Ireland’s surf spots. Brendan and Brian, both engineers, are pragmatic and fluent in Spanish. Bets, a data scientist, always has a backup plan. Between them, they embody the calm and logic I lack.

Our journey to Peru coincided with the president’s arrest, placing us in the midst of national protests, train strikes, and roadblocks. As a result, we opted for a less conventional route to Machu Picchu: a back-road taxi ride through Peru’s mountainous south.

The plan seemed simple: drive five hours from Cusco to Hidroeléctrica, the closest point to Machu Picchu reachable by car. From there, hike two hours to Aguas Calientes, stay overnight, see Machu Picchu at dawn, and return to Cusco in time for our flights. What could possibly go wrong?

By the time the protesters dismantle the roadblock and leave, chanting “¡Viva el paro!” the shadows are long. Drivers honk their horns in celebration, and the tension of waiting evaporates. We pile into Wilbert’s trusty Toyota Yaris, a 2005 model showing its age. He hits the gas.

In the car, Bets and Brian trade travel stories while Wilbert and Brendan discuss politics, history, and sports. Wilbert, plugged into a WhatsApp group of local taxi drivers, gets real-time updates on protests and road conditions—information far ahead of official sources.

As we climb into the Andes, the road twists and narrows. At 4,000 meters above sea level, we pass through misty clouds, surrounded by towering mountains that plunge into sunlit valleys. The Urubamba River roars below, fed by glacial melt, as it winds toward the Amazon. Hours later, we descend into the humid cloud forest, where ferns and rhododendrons dominate. Day fades into night, and smooth tarmac gives way to gravel and dust.

In Santa Teresa, a small town near Hidroeléctrica, we stop for dinner. It’s too late to start hiking. I call the airline to reschedule our flights, but after two hours on hold—translated by Wilbert—we’re told it’s impossible. Brian’s quick research reveals that the trains from Aguas Calientes to Cusco are running again. Bets and I can catch the 1 p.m. train tomorrow and make our evening flights.

Midnight finds us navigating the strange choreography of arriving at a stranger’s home. A restaurant owner, after closing up, leads us by flashlight to a nearby guesthouse. We tiptoe past kittens asleep on the stairs, and I brave a quick shower in icy water, dodging a grasshopper near the drain.

The room is sparse, with five beds lined up like a boarding school dormitory. Brendan’s feet dangle over the edge of his bed. “Every time,” he mutters. Next to him, Wilbert is already snoring, exhausted from navigating winding roads and relentless questions. Rain patters on the tin roof above—a grounding, familiar sound.

At 4 a.m., five alarms go off simultaneously. Groggy but determined, we pile back into the car and reach Hidroeléctrica just as the first light of dawn breaks.

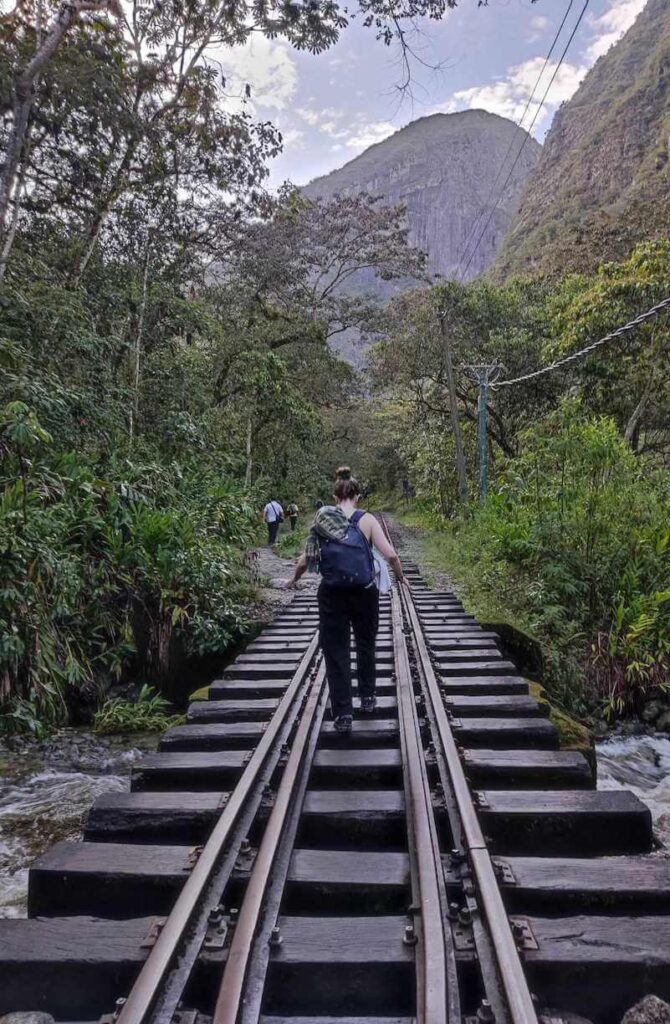

Adrenaline fuels me as we begin our hike. The Andes unfold around us in lush, green waves under a sky that shifts from darkness to light. We walk quietly, soaking in the rhythmic symphony of wind and river. The path follows train tracks through groves of cedar and muña, their scents mingling in the cool air.

As Aguas Calientes comes into view, a train barrels past us, its rumble filling the valley. Brendan pumps his fist and cheers, his excitement contagious. Machu Picchu awaits.

Our entry tickets to Machu Picchu allow access to different routes, so we part ways where our paths diverge. As we say goodbye, I reflect on how travel forges bonds between strangers, offering a trust and closeness that feels like years of friendship. Brendan’s credit card details are saved on my phone, and I can still recall the rhythm of Wilbert’s snores. I wonder how Andean icecaps transform into the waters of the Amazon thousands of kilometers away, or how five people from three corners of the world managed to cross paths at this precise moment in time.

I know we’ll likely never see each other again. I want to say something profound, something that captures the significance of this shared journey, but the words catch in my throat. Instead, we share a final hug, turn, and walk away.

Bets and I climb to the summit of Huchuy Picchu, one of the viewpoints overlooking Machu Picchu. The air is warm and thick, like honey. Butterflies glide past, their delicate wings shimmering in the sunlight. Below, stone terraces and towers rise in defiance of time, surrounded by mountains crowned with drifting clouds.

Bets pulls a mango from her backpack and hands it to me—a perfect, golden fruit, ripe and bursting with sweetness. I take a bite. For the first time, as time seems to pause, I realize I don’t mind at all.